Loading... Please wait...

Loading... Please wait...- Home

- Author

Author

Garfield on Garfield

I am going to write

In January 1984 I wrote my future with the following entry in my diary:

I think I have come to an important decision in my life - I am going to write. I always thought of my engineering career as a stepping-stone and a foundation to fall back on – writing is now the horizon to which I march.

Looking at this now, after nearly twenty years, I am amazed that I could have been so bold.

It is a very difficult thing to want to be a writer in Jamaica; especially if you want to be great. It seems pretentious and ambitiously ambitious, ridiculously vain, a head-in the-air, pie-in-the-sky type of folly. Writing is not for poor people to do. It is for those of a lighter cast, white people, rich people, foreign people, but not people like me- ordinary people- for whom just growing up is a struggle. Besides, it is not something that you share with your friends. I knew no writers. There was no one to discuss it with. There was no precedent in my community, not for writing, not for any kind of success. Those who succeed, leave.

And yet it confirms to me that as melodramatic as it may sound, we write our own destiny. The moment I wrote that down and convinced myself of what I wanted to be and how I was going to do it, events were set in motion that would get me to where I wanted to go irrespective of the poverty in which I lived.

So I have taken it upon myself to be a writer, not a popular - love or sex-on-the-beach writer, but a serious writer. Not obtrusively academic, but popularizing the archives of the Caribbean people with quality work. I longed to read stories about me and my people. No one was writing them, so I would. That was that. The stories must be told and Jamaicans will read them if they can identify with them. And whether or not they read them, still, the stories must be told and that is my calling. And every story I write - no matter how short or how long it is - every story I write I stop halfway through and question my sanity and whether anyone will want to read it, or why should anyone want to read it, or who do I think I am to assume this mighty role. Whatever… it consumes me and I cannot but do it.

a writer! YOU?

My family was so poor that my mother taught us that the best way to combat hunger was to lie on our bellies. It works too! There were eleven of us in a two-bedroom house with three beds. My mother did not work and my step-father sold fudge & ice cream. I had to sell Kisko (icicle frozen in a baton shaped plastics bag) on the street, to make money to go to high school. For a while I also sold glasses in the market. But that venture didn’t last.

Most of the time, there was no electricity at my house. I remember early that my parents would insist that I turn off the lights in the nights when I studied, because they feared it would send up the light bill. When the light was finally cut off we used candles and a kerosene lamp. I had to buy candles to study and hide them till everyone had gone to bed. My parents would at times take them away to share with the family. It was selfish to want to have candles all to myself – even though I had saved my lunch money to buy them for studying. For my last years at St. Andrew Technical High, the school gave me uniform and food on a special welfare program and paid for my O-level exams.

When I left high school, I had three O-levels: Math, English, and one other. Engineering. This was hardly enough to enter any tertiary institution. Yet when my parents insisted I get a job having finished high school because it was time for me to support the family, I drew the line. I told them there was no away I was not going back to school. I wanted to break the mould and I hated that I had been groomed as the meal ticket. Everyone was waiting for me to leave school get a job and support them. I did take on the responsibility manfully and supported them for years with all I worked.

But I wanted so much more from life. I wanted to be something more.

I remember one evening, sitting under that ackee tree at the back of the yard with my step-father for a man to man talk. He asked me what I wanted to be. I told him I wanted to be a writer. He laughed so much I still remember the sound of his voice grating against the evening. He was a man who could not read, and whose efforts at prosperity lay in increasing his poverty by having more children than he could afford to raise so that he would have them for his old age pension. For a man such as this who fed his family as much on the grace of his neighbours and the goodwill of the shopkeeper down the road, as he did by his own sweat, my utterance, clearly, must have been the most ridiculous thing he could ever hear. The worst part is, I told him how and by when. Similar to what I wrote in my diary, I told him that by forty, I would retire and write my books.

I remember too, at thirty, when I retired from my job as a senior executive at the Maritime Institute to take up my scholarship at The University of Miami to pursue an MFA in creative writing, ( by this I had already won one competition, and had had a few stories published), that he called me aside one day and looked at me beaming with wonderment. I still remember his words. “Man,” he said, “you really do it, you remember, you tell me under that very tree, say you goin’ do it, and Jesus Christ, you do it - with ten years to spare.” I tried to tell him that it was just the beginning I was not yet a writer. I was going to go to school to become one. But that did not matter to him. I had written stories. They had been published. I had won awards, now I had resigned my job to study writing in America. Everything I said I would do came true. He had never in all of his life seen any one who had dreamed, laid out that dream and made them come true. He was so amazed and excited that there were tears in his eyes.

I am going to write

In January 1984 I wrote my future with the following entry in my diary:

I think I have come to an important decision in my life - I am going to write. I always thought of my engineering career as a stepping-stone and a foundation to fall back on – writing is now the horizon to which I march.

Looking at this now, after nearly twenty years, I am amazed that I could have been so bold.

It is a very difficult thing to want to be a writer in Jamaica; especially if you want to be great. It seems pretentious and ambitiously ambitious, ridiculously vain, a head-in the-air, pie-in-the-sky type of folly. Writing is not for poor people to do. It is for those of a lighter cast, white people, rich people, foreign people, but not people like me- ordinary people- for whom just growing up is a struggle. Besides, it is not something that you share with your friends. I knew no writers. There was no one to discuss it with. There was no precedent in my community, not for writing, not for any kind of success. Those who succeed, leave.

And yet it confirms to me that as melodramatic as it may sound, we write our own destiny. The moment I wrote that down and convinced myself of what I wanted to be and how I was going to do it, events were set in motion that would get me to where I wanted to go irrespective of the poverty in which I lived.

So I have taken it upon myself to be a writer, not a popular - love or sex-on-the-beach writer, but a serious writer. Not obtrusively academic, but popularizing the archives of the Caribbean people with quality work. I longed to read stories about me and my people. No one was writing them, so I would. That was that. The stories must be told and Jamaicans will read them if they can identify with them. And whether or not they read them, still, the stories must be told and that is my calling. And every story I write - no matter how short or how long it is - every story I write I stop halfway through and question my sanity and whether anyone will want to read it, or why should anyone want to read it, or who do I think I am to assume this mighty role. Whatever… it consumes me and I cannot but do it.

a writer! YOU?

My family was so poor that my mother taught us that the best way to combat hunger was to lie on our bellies. It works too! There were eleven of us in a two-bedroom house with three beds. My mother did not work and my step-father sold fudge & ice cream. I had to sell Kisko (icicle frozen in a baton shaped plastics bag) on the street, to make money to go to high school. For a while I also sold glasses in the market. But that venture didn’t last.

Most of the time, there was no electricity at my house. I remember early that my parents would insist that I turn off the lights in the nights when I studied, because they feared it would send up the light bill. When the light was finally cut off we used candles and a kerosene lamp. I had to buy candles to study and hide them till everyone had gone to bed. My parents would at times take them away to share with the family. It was selfish to want to have candles all to myself – even though I had saved my lunch money to buy them for studying. For my last years at St. Andrew Technical High, the school gave me uniform and food on a special welfare program and paid for my O-level exams.

When I left high school, I had three O-levels: Math, English, and one other. Engineering. This was hardly enough to enter any tertiary institution. Yet when my parents insisted I get a job having finished high school because it was time for me to support the family, I drew the line. I told them there was no away I was not going back to school. I wanted to break the mould and I hated that I had been groomed as the meal ticket. Everyone was waiting for me to leave school get a job and support them. I did take on the responsibility manfully and supported them for years with all I worked.

But I wanted so much more from life. I wanted to be something more.

I remember one evening, sitting under that ackee tree at the back of the yard with my step-father for a man to man talk. He asked me what I wanted to be. I told him I wanted to be a writer. He laughed so much I still remember the sound of his voice grating against the evening. He was a man who could not read, and whose efforts at prosperity lay in increasing his poverty by having more children than he could afford to raise so that he would have them for his old age pension. For a man such as this who fed his family as much on the grace of his neighbours and the goodwill of the shopkeeper down the road, as he did by his own sweat, my utterance, clearly, must have been the most ridiculous thing he could ever hear. The worst part is, I told him how and by when. Similar to what I wrote in my diary, I told him that by forty, I would retire and write my books.

I remember too, at thirty, when I retired from my job as a senior executive at the Maritime Institute to take up my scholarship at The University of Miami to pursue an MFA in creative writing, ( by this I had already won one competition, and had had a few stories published), that he called me aside one day and looked at me beaming with wonderment. I still remember his words. “Man,” he said, “you really do it, you remember, you tell me under that very tree, say you goin’ do it, and Jesus Christ, you do it - with ten years to spare.” I tried to tell him that it was just the beginning I was not yet a writer. I was going to go to school to become one. But that did not matter to him. I had written stories. They had been published. I had won awards, now I had resigned my job to study writing in America. Everything I said I would do came true. He had never in all of his life seen any one who had dreamed, laid out that dream and made them come true. He was so amazed and excited that there were tears in his eyes.

All prices are in USD. Copyright 2025 Garfield Ellis. Sitemap | Powered by HB-Commerce

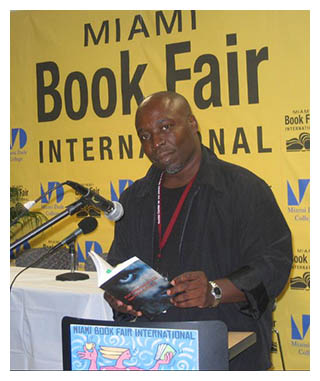

Author's Profile

Garfield Ellis grew up in Jamaica, the eldest of nine children. He studied marine engineering, management and public relations in Jamaica and completed his Master of Fine Arts degree at the University of Miami, on full scholarship as a James Michener Fellow.He is a two-time winner of the Una Marson prize for adult literature; in the first instance for his first collection of short stories, Flaming Hearts (pub. 1997), and later for the still unpublished novel, Till I'm Laid To Rest. He has twice won the Canute A. Brodhurst prize for fiction (The Caribbean Writer, University of Virgin Islands) 2000 & 2005 and the 1990 Heinemann/Lifestyle short story competition.

Garfield is the author of five published books: Flaming Hearts, Wake Rasta, Such As I Have, For Nothing at All and Till I'm Laid To Rest, Spring 2010. His work has appeared in several international journals, including; Callaloo, Calabash, the Caribbean writer, Obsidian III, Anthurium and Small Axe.